ASG Analysis: A Déjà Vu in the Upcoming French Presidential Elections?

Key takeaways

-

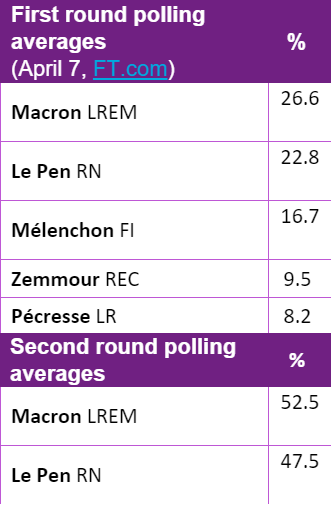

French President Emmanuel Macron is running for reelection. He was elected on a centrist agenda for the first of two possible five-year terms in 2017, easily defeating Marine Le Pen, a nationalist populist. The two are likely set for a rematch – only this time a more competitive one.

-

Macron hopes to become the first French president since 2002 to be reelected, despite Le Pen’s steady gains in recent polling and the potential for a much smaller margin than in 2017. Five years of decisive decision-making and relentless reforms have made him a polarizing choice. He has destroyed both of France’s traditional center-right and left parties by branding himself as “neither left nor right.”

-

The election is taking place as voters are increasingly dissatisfied with French politics, seeing it as elitist and isolated from day-to-day concerns. Le Pen is aiming to change that dynamic by focusing on bread-and-butter issues like inflation and avoiding criticism over her ties to Vladimir Putin, as the other pro-Russia candidates have dipped in the polls. Issues over national identity have also played a central role in the campaign, as Le Pen and the right peddle in anti-migration rhetoric and Macron tries to play up his role as a statesman representing a bold France abroad.

-

A Macron reelection, even if narrow, would signal continuity for France and Europe in turbulent times. At home, he would continue championing reforms, industrial policy, and modernization of the economy. Abroad, France would continue to push towards more EU integration and a stronger European role on the international stage. Le Pen would drastically upend this dynamic, souring relations within the EU and across the Atlantic.

-

Even if Macron can manage to be reelected, French politics has shifted far to the right, with three out of the top five candidates representing right-wing views, and Macron himself showing a rightward shift in both social and economic policy over his first term. Having definitely not had an easy first term in office, a second one could potentially be even more challenging.

Race overview

The French presidential elections occur in a two-part contest on April 10 and 24, followed by two rounds of legislative elections on June 12 and 19. For both the presidency and district-based seats in the National Assembly, the first round determines the two contestants for the runoff. Due to France’s centralized presidential political system, the most crucial contest is the presidential race, where incumbent President Emmanuel Macron is running for reelection.

After five turbulent years in power, Macron remains the favorite to lead the first round and win a second term in the runoff, although storms are brewing on the horizon. His time in the Élysée Palace has been defined by a slew of legislative achievements – including tax, labor, and public sector reforms – that have been overshadowed by the gilets jaunes (yellow vest) protests, pension reform strikes, a diplomatic spat with the U.S. over AUKUS, a failed military mission in Mali, the Covid-19 pandemic and anti-lockdown protests, inflation, and more recently Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, where Macron has tried to play the role of an international statesman. With each challenge, Macron has wielded his influence for a compromise-driven solution, making him the candidate of palatable stability for some while also diminishing enthusiasm from an already disillusioned electoral base. Macron’s centrist party, La République en Marche! (LREM), is expecting Macron to mobilize an unenthusiastic electorate to victory in both elections, with the legislative almost always won by the winning presidential candidate’s party. Macron only began campaigning in earnest in the last few weeks of the election, drawing concern from his own bloc, as he instead tried to show himself as above politics and as a stable hand dedicated to addressing the war in Ukraine and Covid. But Macron is not without certain vulnerabilities, especially the widespread perception he is an out-of-touch elitist, further validated by the launch of an investigation in the last days of the campaign into his government’s extensive use of external consultants, dubbed “McKinsey-gate.”

Enter Macron’s main competitor: Marine Le Pen, his 2017 runoff rival, who has attempted a rebrand as a more reasonable nationalist and populist candidate. Despite remaining true to her long-standing approach of right-wing politics and xenophobic rhetoric, her image has been rehabilitated by purging the most radical elements of her Rassemblement national (RN) party and by the candidacy of Éric Zemmour, a former pundit known for a more incendiary form of conspiratorial far-right politics. Le Pen has also shrugged off concerns about her links to Russian President Vladimir Putin, pledging not to interfere in Russia’s war in Ukraine and to block sanctions against Russia, avoiding economic costs to France. Le Pen’s rise in the polls in the days before the election likely stems from voters switching from lagging right-wing candidates and from news of rising inflation, raising alarm bells across Europe for fear of a repeat of the 2016 U.S. election. Le Pen could also benefit from the possibility that enough voters on the left, discontented with either of the two choices, will abstain from casting their votes in the second round.

Shifting polls have affected the remaining candidates as well, adding to the uncertainty of the election and affecting likely endorsements for the second round. Currently in third place, Jean-Luc Mélenchon from the far-left La France Insoumise (FI) party is the only candidate on the left polling above 10 percent and is trending upward; he is anti-NATO and eurosceptic, all rooted in nationalist, left-wing, and activist environmentalist politics. Zemmour, who was surging last year, has taken the largest dip in the polls, paying the greatest toll for his pro-Putin views and incendiary rhetoric. Valérie Pécresse of the once strong Les Républicains (LR) party represents a narrow band of conservatives not coopted by Macron or the far right, and is a diminished presence in the race. Member of the European Parliament Yannick Jadot of the Greens and Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo of the once dominant Socialists round out the flailing remainder of the French left, polling in the low single digits.

Key issues

French voters are broadly disinterested in the election, which has received little media coverage, reflecting disenchantment with the political system. Nonetheless, key issues for the presidential elections include:

Economy. Despite a strong economic recovery so far from the Covid-19 pandemic and relatively low unemployment levels, voters feel a sense of precarity. Media discussions are increasingly focused on the economic cost of Russia’s war in Ukraine and high food and gas prices, a particularly sensitive topic since the gilets jaunes protests were prompted by a proposed gas tax. While environmental policy is a voter concern, most believe they should be insulated from high fuel costs, so Macron is promising €50 billion in nuclear power and the green transition as a remedy. Whether or not some of France’s taxes should be repealed or cut is subject to recycled debates on fiscal responsibility, but every major candidate is promising to reduce ordinary people’s tax burden and there is little fighting about the specifics. Another key issue is pension reform. French workers are religiously attached to the country’s low retirement age of 62, and reforming pensions risks touching a third rail. Nevertheless, Macron is vowing to try, in the name of preserving France’s social contract.

Immigration and the so-called culture wars. Backlash to France’s shifting demographics has led to increasingly tense rhetoric around national identity and “laïcité” secularism, often presented as concern about inserting race and religion into French life, as discourse on criminality and law enforcement, or, coupled with anti-Americanism, as fears of importing so-called wokisme. Right-wing candidates criticize Macron and others for supporting non-French (read: American) ideas, also deriding home-grown social justice movements. The criticisms have prompted Macron’s assertion that he is against “woke culture” and even led to government policies fighting supposed “Islamic separatism” and “Islamo-leftism.”

The culture war debates are a broader reflection of identity-based concerns about immigration. Because many of the perpetrators of the terror attacks of the 2010s were portrayed as foreign threats, pundits and politicians regularly link security to non-European migration, making it an existential question for voters on the right. So, Pécresse vows to curb immigration, Le Pen halt it, and Zemmour reverse it, while Macron is content enough with “controlling” it.

The EU. Despite the country’s role as a key player in EU decision-making, French voters are tacitly eurosceptic, often in defense of French notions of sovereignty. However, Macron remains an unapologetic supporter of the European Union – a key theme of his 2017 campaign. The issue is one of the few, if any, issues being substantively debated, even if most voters agree France should lead Europe. Macron aims to carefully manage the public’s perception of EU integration, often tying it to his broader vision for France in the world: reining in big tech; strengthening EU defense, borders, and security; and rationalizing bureaucracy. Zemmour and Le Pen fervently oppose European integration and call for reduced EU responsibilities for France, although that is a softened stance for Le Pen, who used to advocate for a “Frexit” from the Union and Euro.

Views of the EU are also reflective of the candidates’ stances on responding to the war in Ukraine, especially on sanctions and strengthening European defense. Macron is strongly in favor of an ambitious Western response and has supported tough EU sanctions against Russia, provided military aid to Ukraine, and stepped up France’s military response within NATO; Zemmour, Le Pen, and Mélenchon want to roll back sanctions; and Pécresse wants to stay the course.

Outlook

The elections come at an interesting time for France: The public is broadly uninterested, much of the media coverage is absorbed by the horrors of the war in Ukraine, most Covid-19 restrictions have been lifted (but the BA.2 sub-variant is spreading through Europe), and the otherwise strong economic recovery is hampered by inflation.

A Macron victory, even if a narrow one, would validate his style of politics: think loudly, negotiate intensively, and quietly compromise. Domestically, it would enable him to continue to pursue aggressive state intervention in strategic sectors of the economy, reform the public sector, digitize and green the economy, and fight for French industry. Abroad, he would continue to aim for EU strategic autonomy and a stronger Europe in the world, especially considering the war in Ukraine, always seeking to balance both economic interests and a push for security and democracy. With both the French and German elections out of the way, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Macron would have the opportunity to strengthen their own fragile coalitions at home through EU-level victories. Macron’s foreign policy approach may occasionally cause brief flare-ups with the Biden administration, especially when French industrial interests are at play. Even so, the trans-Atlantic relationship could be expected to continue delivering results, like the recent Boeing-Airbus agreement, progress in the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, and a new data transfer agreement. Overall, Biden would likely continue to find an ally in Macron, even if he might occasionally show characteristically French reluctance to go along with Washington.

On the other hand, a Le Pen victory, or an unlikely Mélenchon or Zemmour one, would be hugely detrimental for France’s role in Europe and across the Atlantic. At home, Le Pen would struggle to muster a legislative majority, paralyzing her presidency as soon as it began. In Europe, it would constitute the biggest hitch for the EU since Brexit, bringing to halt most of Macron’s ambitious ideas about EU reform and upsetting relations with Germany’s ruling center-left government. A Le Pen win would also raise very serious questions about the EU’s unity over sanctioning Russia, with Le Pen unlikely to find many allies beyond Hungary’s recently reelected Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Le Pen’s controversial views on topics like Russia, NATO, and sanctions would also quickly sour the relationship with the Biden administration.

Emerging trends

Regardless of the winner, the election will be the final nail in the coffin for France’s mainstream political parties, Les Républicains and the Parti socialiste¸ a trend that started in 2017. Both parties’ candidates combined are expected to only receive about 10 percent of the vote, pointing to a highly fragmented political landscape. A victorious Macron could easily poach the political figures in both parties who have any aspirations for national-level politics (though some on the right may join Le Pen’s camp), while the remainder will quarrel with their local party bases for meager local positions and the occasional seat in the European Parliament.

The election will also show that right-wing populism is still a force to be reckoned with in Europe. Despite countless predictions of its demise due to recovering economies, Covid-19, or the war in Ukraine, right-wing populists prove to be formidably resilient with renewed strength in some countries (e.g. France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Belgium, Sweden, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania, and Estonia) while weaker in others (e.g. Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, and Greece). A Le Pen victory would only embolden populist movements further while weakening the EU’s recently agreed-to conditionality mechanism that cuts off EU recovery funds for countries where autocratic governments have weakened the rule of law.

_____________________________________________________________________________

About ASG

Albright Stonebridge Group (ASG), part of Dentons Global Advisors, is the premier global strategy and commercial diplomacy firm. We help clients understand and successfully navigate the intersection of public, private, and social sectors in international markets. ASG’s worldwide team has served clients in more than 120 countries.

ASG's Europe practice has extensive experience helping clients navigate markets across Europe. For questions or to arrange a follow-up conversation please contact Pablo Rasmussen.